In my search for unusual characters to feed my Buenos Aires chronicles, my friend Marion mentioned that her son Dani had an activity with children that might interest me.

I got in touch with him and found his project, Bote al Agua, fascinating: a workshop for learning mathematics for kids by building a boat! So my video assistant Lucas and I went to spend a morning of total immersion at Bote al Agua. The carpentry workshop is located in Tigre, in a huge area populated by artistic and ecological enterprises.

We met Dani, the creator of Bote al Agua, six 11-year-olds finishing elementary school, Celeste, the teacher of a self-managed school in Tigre, and Julián and Denise, the two teachers.

That morning, we were able to see first-hand how a different approach to teaching can be put into practice.

A fascinating morning!

Le Tigre

The Tigre Delta in Argentina is a region located in the province of Buenos Aires, some 30 kilometers north of the city of Buenos Aires. The region is characterized by its river islands, canals and marshes, which are fed by the waters of the Paraná delta. The Tigre Delta in Argentina covers an area of around 9,000 km², with a permanent population of around 7,000 living on the river islands. This makes it one of Latin America's most important deltas in terms of biodiversity and tourism development.

The region is frequented by tourists from Argentina and abroad, who come to enjoy the beaches, water sports, local gastronomy and artisan markets. The Tigre Delta is a unique and peaceful region, offering a different experience from the hustle and bustle of Buenos Aires.

Source: GPT chat

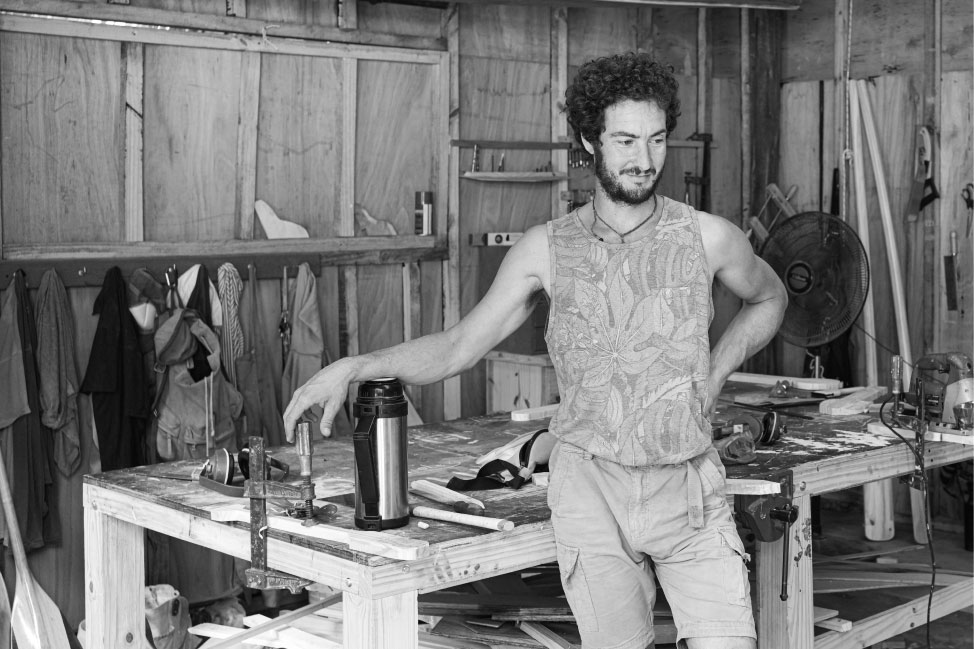

DANI

Can you tell me about your background?

My professional life at 100% has been linked to journalism, mainly economic and financial, and communications in technology companies such as Google and Facebook. For years, I worked in the downtown areas of Buenos Aires, but I always dreamed of my weekends in the Tigre Delta, where I have a house, a boat and my feet in the mud. That's the B side of my personality.

The story began years ago when I became interested in wooden boat building. In Argentina, the tradition is being totally lost. There are still the beautiful lanchas colectivas (boats that transport people) and the boats of rowing clubs.

But plastic and fiberglass have replaced wood in most boats.

Perhaps my interest in this type of construction is linked to a typical sixty-something nostalgia for a time when we had the time and patience to keep alive a very noble craft tradition.

As I couldn't find any courses in wooden boat building in my own country, I enrolled in an American school in the state of Maine. It was a "summer camp" with a shared bedroom, dining room and bathroom, and intense work: from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., workshop work to build a boat, complete carpentry, dust, shavings; very physical work.

As the school also offered a course on working with children, I decided to take it because the idea of setting up a children's workshop at Le Tigre seemed very powerful. And so, in 2019, I set up an NGO, Bote al Agua.

Here is the presentation of our activity on our website https:/botealagua.com

Our work proposes project-based learning (PBL), a method by which children incorporate knowledge around a task that takes them out of the traditional student-teacher relationship and places them as protagonists in a project that interests and amuses them. At Bote al Agua, we build wooden boats as a team.

In our workshops, children are introduced to mathematical concepts, relating the discipline to its practical utility through direct experience. They also learn to use hand tools, plan, work as a team and achieve their goals. The highlight of each workshop is taking the boat to the river and paddling as a group.

Many topics can be covered while building a boat, the most obvious being geometry, because when you're building a boat, you're making triangles and other geometric shapes, measuring right angles, talking about symmetry, and algebra because you're dividing and adding.

But we also talk about physics, about why a boat floats, about Archimedes, about the characteristics that make it float better.

We do tests in buckets of water: we put up model boats and float them, putting weights on them with screws and nails to show them how, through practice, a boat that weighs nothing can resist in an incredible way. All these things are very visual, and children won't easily forget them.

In this type of project, pedagogy seems to be essential.

Yes, of course. I took an American course with an exceptional teacher, Joe Youcha (see his website building to teach.com/ joe-youcha-director).

I also did a lot of personal training. In particular with Marcelo, a math teacher who had taught my daughter in high school. When I called him, he asked me " why you want to do math at your age ? ". When I told him about the project, he understood and agreed. We worked together for a few months and he gave me good advice on what to teach and how to teach it.

Do you have any collaborators?

Yes, I have a team of 5 young people working in the workshop, some with more woodworking experience than others, but all with a vocation for teaching. The most important thing is to know how to work with children, to make lessons fun and enjoyable. Today, you'll meet Julián and Denise.

What kind of schools take part in the workshop?

The children come from public and private schools in different places, not necessarily in Tigre. Sometimes we mix public and private schools in the same class, with very interesting results.

Recently, a mother said to me: "I'm very grateful to you because, in addition to the educational work, when you build the boat, there's no fracture (grieta)". She wasn't referring to politics, but to the social divide. She told me that building the boat makes everything equal, that it erases social differences. That's one of my goals.

Paradoxically, many poor children from the mainland don't have access to the river. The river is for islanders and for wealthier people who spend weekends in their own homes or go to a rowing club. For children living in poor neighborhoods, building a boat means " You can also connect to the river and take a boat out. "

How do children react?

In general, they respond very well. In fact, the concept is that children are the protagonists of their work, because the boat is made by them, it's designed to be built by children with hand tools, doing fun things like cutting, measuring, nailing, screwing and gluing.

Normally, all these activities are interesting. Usually, when they hammer, half the nails don't go in properly, they bend, or the children hit next to the nail. The children then look at you with a guilty expression, as if they've done something wrong. We then say to them: " Never mind, just throw it away and start again." . They relax. They learn to make mistakes without guilt, that they can be corrected.

Everything ends up being like a game, fun, where at the same time you're reviewing concepts relevant to education at this stage of school. You say "We said the angle is right, how do we measure it? The angle is right, measure it with a square. Is there a little daylight? There must be a little more than 90 degrees? it doesn't matter. "or " these two sides are not equal, they are not congruent. The boat must be exactly the same on one side as on the other, symmetry is the basis of a boat, you have to remake this piece".. All this happens so naturally that the children may not even have noticed that they were learning all these concepts.

And when we ask them " what did you like?"many answer "The truth is, I'm proud of what I've done with my classmates. I never thought I'd be able to do a job like this."The feeling is that they've done something out of the ordinary, because a boat is an object that you can use, that supports you, that transports you, it's an essential object, especially in the Tiger....

In this workshop, unlike in schools, there are no cell phones, because you can't build a boat with a phone in your hand! There's paint and dust, and the children protect it. I also want to believe that it doesn't appear because the children are doing something that amuses and entertains them.

What's more, what they learn can be useful in their everyday lives. A young girl who lives in a shantytown very close to our workshop was cutting out the seats for the boat and suddenly said "this is like what I wanted to do for my bedroom, because I need a little bookcase...".

And how long is the course?

It's very flexible, but generally 12 lessons of 2 hours each. At one lesson a week, that's about three months. As the boat quickly takes shape, children remain highly motivated during this period.

How is the workshop financed?

So far, it's a combination of my own money, money from contractors who have lent me a workshop, occasional donations and the sale of the boats we've built, which enables us to recoup the price of wood and other materials.

Recently, I've started opening the workshop to private schools who pay me for the course.

For the time being, we have not received any subsidies from the Municipality or the Ministry of Education.

Which school is coming today?

Today, you're going to meet a very special, self-managed school, created and run by islanders.

School children

Bote al Agua teachers

What's your itinerary? How did you get to Bote al Agua?

I was working in Misiones as an environmental guide in a private reserve. I offered hiking, kayaking, visits to Guarani communities and other typical activities. In this reserve, I met a Tigrayan woman, we started a relationship, and after a year and a half, I moved to Tigre. I had been living in Rosario, on the banks of the Paraná River, where I had a kayak and went as far as I could. So coming to Tigre meant returning to familiar territory. A year and a half ago, a friend introduced me to Dani, who told me she had a project linked to boats, the river, teaching... everything I love. We started working together and I've been with him ever since.

Then came the pandemic and the confinement, first for 15 days, then 1 month, 2 months, and finally two years. One day, Dani called me and said: "Hey Juli, we're going to have to activate this because having an unused workshop is a waste, I suggest we do something on our own, make a different boat.". So the two of us embarked on a great project and built a much bigger boat that can run on a motor, a boat we called Ruperta in homage to Ruperto Massa, the name of the street where we're located. We also built a smaller one, like an island canoe, which I use every day to get to and from the island where I currently live. Every day, I come with "Renata", which is the name of Ruperta's granddaughter, with my bike to pedal from the quay to the workshop.

Is this your only job?

I work here from Monday to Friday. At weekends, I work on the island, in cottages or on guided kayak excursions to discover the flora and fauna of Tigre.

How did you get to Bote al Agua?

I studied cinema, nothing to do with what I'm doing now! I'm Jewish, and as a child I used to go to the Bnei Tikva community in Belgrano. At that time, I was already interested in everything to do with education, I gave classes to groups and I was also interested in everything to do with carpentry.

I met Dani at a social event. He told me about his project and it was as if everything I loved came together: education and carpentry. And that's when we got started. Dani had just obtained premises and we began building the first boat, "La Clota".

Have you given up film altogether?

Yes, completely. As well as working here, I have a workshop in my house where I make furniture. And I give carpentry courses for adults.

I've noticed that you're a great teacher.

Yes, I get on very well with the children, but I've never studied anything to do with pedagogy. I just try to put myself in their place, I put myself in the place of the children who come to play and I connect with them. I feel that if I come to play, they play too.

How old are the students who come to Bote al Agua?

The children you see here today are finishing elementary school, aged 11-12. But we also have two schools finishing high school. At this age, it's even more interesting because, as teenagers, you get the impression that nothing makes sense, that the world is horrible, and they come here with a lot of mistrust. Very quickly, they become totally involved. It's an activity that helps them to structure themselves.

How do you feel about this experience?

The truth is that sometimes I can't believe it, it's like I've found something that feels like a joke, a dream.

When people ask me " what I do for a living" I feel like answering " I'm going to spoil your day if I tell you what I do for a living, because I'm sure you'll think my work is better than yours and envy me." .

I don't work, I enjoy myself. Work is logistics before the class, but when the class starts, it's no longer work, especially as we're in this magnificent space, with a small team and no hierarchy.

Does your name, Denise, have a origin French?

I don't think so, they were going to call me Laura and my grandmother came running into the hospital and said "please don't call her Laura, call her Denise".

At the end of the day

It was my last day in Argentina. The visit to the Bote al Agua moved me. What did I feel? Harmony, good vibes, freshness, naturalness, positivity. As Denise said, it felt like a joke, like a dream.

It was a morning spent with "beautiful" people, united around an exciting project. A real pleasure.

As I progress in my chronicles, I realize that the qualities I observed this morning - generosity, creativity, the desire to move forward, openness, positivity - are not exceptional, they are qualities shared by many, they are like a dough common to many Argentines. It is this side of my compatriots that I want to continue to deepen and enhance in all their diversity.

Especially when these personal qualities are at the service of an original and inclusive company, a project with a social and solidarity vocation.

I'm discovering a generous, positive and enterprising Argentina, which I appreciate and want to illustrate in these columns. It sounds interesting. How about you?

LOS BIGUAES" SCHOOL (named after an island cormorant)

I had the opportunity to interview Celeste, one of the teachers at a self-managed island school. Given her interest, I decided to include the interview in my column on Bote al Agua.

How does the school work?

We are a self-managed school located on the Carapachay River in the Delta. The school is supported by the work of the families, who bake bread in the morning and sell it afterwards. We are not supported by any government or municipality. We have no legal existence, we are a de facto school and not a school with legal status, but we teach the same subjects as public schools. We've been in operation for 14 years, and these children are Class 8.

When they finish elementary school, they have to take a very comprehensive exam in the city of Buenos Aires that covers the four fundamental areas, language, mathematics, social sciences and natural sciences. The students here have all passed. In general, children who go on to secondary school do very well.

There are 60 such schools in Argentina. We have no service or administrative staff. All tasks are carried out by the teachers with the boys and girls. The children are given cleaning tasks, such as sweeping the hall, cleaning the bathroom or emptying the garbage cans. This week, for example, one child is in charge of making sure there's always toilet paper in the toilets. Periodically, we take turns. At lunchtime, we have a snack that we all prepare together, usually tea or maté cocido and food that has been prepared at school or that someone has brought to share, or that we cook together.

How did you get to this school?

I was studying biology, but during an exchange program with the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Cordoba, I was invited to visit an experimental school which I found marvellous. I decided to change direction and trained as a teacher for this type of school.

I'd love to write a column about this school!

Leave a Reply